May is Foster Care Awareness Month, a time when we commit (or recommit) to understanding the conditions and needs of some of our most vulnerable citizens. But beyond educating ourselves, what can we do to help?

This is the part where I’m supposed to encourage you, dear reader, to become a foster parent, to “be there for a child” or “change a life.” Unfortunately, it’s not that simple.

I don’t mean to be glib. In some ways, it really is that simple: A child needs a safe, loving home, and an adult (or adults) with the desire to parent steps up to provide it. But to truly show up for our kids, we need to do much, much more.

I was a foster parent in 2014/15. The experience was transformative for me. It taught me more about love than anything else I’ve ever done or been through. Yes, it was hard. Yes, it was messy and exhausting and it required me to stretch in ways I didn’t feel ready to. But the emotional toll, the love and loss – and yes, occasional drama – were human experiences that deepened my compassion and helped me grow. Interacting with the Washington State Department of Social and Health Services was the exact opposite.

Here’s the thing: I believe in caring for children in need, in making room in our homes and hearts and learning what it means to love someone — not with a particular outcome in mind, but just for the sake of it. I believe in the overused aphorism “it takes a village to raise a child” all the way to my core. These beliefs are what drew me to foster care. But to be a foster parent, you must participate in the foster system. And the foster system is deeply, deeply flawed.

And it’s no wonder. Our child welfare system is only as healthy as the culture it has grown out of, and – despite the “family values” rhetoric of some politicians — our culture does not prioritize families. Instead we prioritize profit, allowing “the market” to dictate who has access to human necessities like food, shelter, health care, and education.

Kids are placed in foster care when their families of origin are unable to care for them. In about 35% of cases, this is due to physical or sexual abuse. In the other 65%, it is because of neglect, which can happen for all kinds of reasons. Some parents struggle with addiction; others simply lack the resources to meet their children’s material needs or provide the supervision our culture currently deems appropriate. (We must remember that norms for supervision are extremely contextual and also that our current expectations require time and money that many – perhaps even most – families do not have.)

Child welfare systems across the US have a history of harming people of color — in particular, African American and Native American families. This harm has happened in egregious and obvious ways — Native American boarding schools, for example — and in subtle, insidious ways, such as the overrepresentation of children of color in foster care. In Washington State, Black and Native American children are removed from their families of origin at higher rates than white children, even when their living conditions are the same or similar. (And, of course, families of color are also disproportionately harmed by other systems, which makes them more likely to have contact with the child welfare system in the first place.)

Foster care, like many other critical services in Washington State, is underfunded. Social workers have more cases than they can handle and not enough resources to provide essential services. This means that even dedicated and well intentioned social workers will not have enough time or context to make informed decisions about what is best for a child’s future, and even when they do, they will not have the ability to meet every child’s needs.

So yes, we should show up for kids right now, as foster parents and mentors and even perhaps as social workers. (People of color, it’s especially important for us to show up.) But we must understand that serving the system as-is will not create the wholeness we are seeking for our children. We also must be willing to do the harder work of building a society that truly supports their well-being.

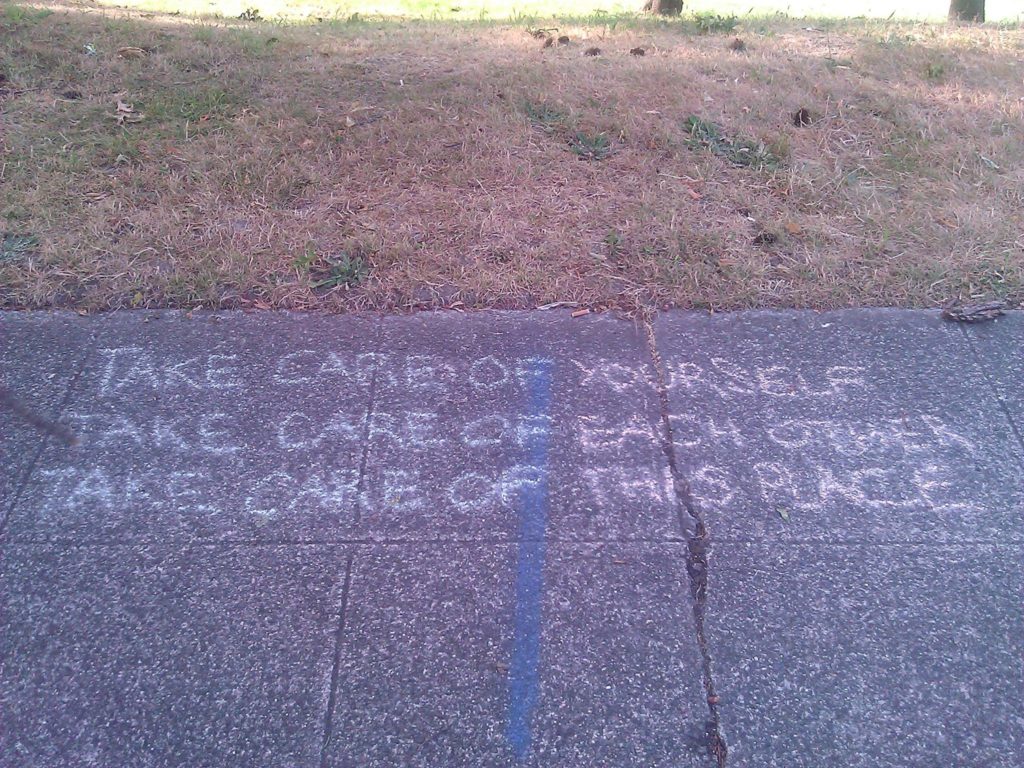

The best thing we can do for children is to sustain the families they were born to. This means we must build a society that prioritizes people, where living wage jobs, health care, child care, housing, accessible transportation, safe streets, and humane schools are available to all. We also must work to strengthen our communities, so that families have healthy social connections and can rely on support from friends and neighbors for short term needs or in the event of a crisis.

We must address the racism that is inherent in our child welfare system –- and all of our systems. This means that we must first acknowledge the harm that was caused in the past. We must look with clear eyes at the ways white supremacy and racial bias continue to influence the outcomes we see today. Then, we must commit to changing those outcomes.

And finally, we must fully fund agencies that are tasked with caring for people, particularly agencies involved in the foster system. Because when the state takes the monumental action of removing a child from her family of origin, the state is morally obligated to provide that child the safety and resources she needs to thrive.