Today Chicklet turns 10 years old. My tiny little bus buddy is now a fourth grader, a self-described “horse crazy girl” who loves Prince, PAWS, books, trees, her baby cousins, and politics. Seriously, politics. She is the kid who insists on helping me fill out my ballot (which reminds me: gotta get on that), who enjoys watching debates and could easily name every elected official who represents her, from the senate to the city council. Despite her introverted nature, Chicklet wants to be one of those elected officials someday — and not just to make the world a better place. She has admitted (more than once) that she wants to “be in charge of people” just for the sake of it.

I digress.

Having a decade-old daughter means I’m 10 in bus mom years. I’ve learned a lot of lessons in 3,653 days of life on the ground — schlepping stuff and managing disasters (mostly minor) by bus. Here are 10 of them.

1. Creativity and flexibility are a bus parent’s most important tools. There are plenty of parenting practices — and even some products — that will make busing with kids easier. But the key to a successful bus parenting experience is an ability and willingness to adapt to whatever circumstances you are presented with.

Long bus wait? Play Connect Four. Heading to the beach? Pack tiny buckets. Struggling to keep up with youth ORCA cards? Get a lanyard (and a label). Toddler throws up on the 8? Use everything in your bus bag.

2. A plastic bag can solve almost any problem. A plastic bag is an essential item for most bus riders but especially essential for parents. Plastic bags are (unfortunately) abundant, free, easy to carry, and incredibly versatile. They can be used for on-the-way shopping (though these days, I carry an actual shopping bag, too), trash collection (for those random snack wrappers, banana peels, dirty tissues, diapers, etc., etc.); laundry (remind me to tell you about the time Chicklet sat on a mysterious brown substance at a bus shelter downtown), seating (to cover wet benches or ledges), and even, in a pinch, vomit (expelled by sick kiddos or those unfortunate individuals who are busing while pregnant).

Even if you’re not great at packing, it’s easy to keep at least one plastic bag in your backpack, purse, or pocket. And it’s worth it. Reduce, reuse, recycle.

3. Busing prepares kids for life. Several years back, I wrote a post about how busing makes kids smarter. It might have been a bit of a stretch (and it definitely scored high on the smug scale), but I am convinced that bus kids are more ready for the world than kids who are driven everywhere.

Busing involves waiting. In the early years, this can be challenging, but kids do get used to it. They learn how watch the world, or daydream, or make conversation, or read a book when they’re bored. This comes in handy when they’re in line at the grocery store, in the dentist’s office, at a restaurant, or pretty much anywhere kids are expected to keep their bodies calm and minds occupied for more than 30 seconds.

Bus kids build physical stamina from all the walking they do. Kids who walk a lot are healthy, ready for almost any outdoor adventure, and able to keep up with parents on shopping excursions and other walk-intensive outings.

A Monday walk to school

Bus kids learn to navigate at an early age and develop an intimate, on-the-ground knowledge of their community. This prepares them to get around on their own long before they are old enough to drive.

Bus kids learn to interact safely with people they don’t know. They practice setting and respecting boundaries, and they are exposed to people of all different ages, colors, orientations, incomes, temperaments, and abilities. This helps them understand that everyone belongs. And the way I see it, there’s nothing more important to learn.

4. Policies matter. Back in the dark ages, when my kids were still portable, Metro’s stroller policy required parents to remove children from strollers and collapse the strollers before boarding the bus. This made some sense from a safety and space use perspective but absolutely no sense from a parent’s perspective.

Long before I became a bus mama, I knew I would never bring a stroller onto the bus if I could possibly help it. And when I did have kids, I wore them in a carrier as often — and for as long — as possible. When they started getting too big to be carried in a pack, I struggled. There was a good six-month stretch when I was willing to walk very long distances in bad weather to avoid the bus, because the stroller hassle was just too much.

The benefit of this excruciating period was that I was very motivated to get my kids walking on their own. Both of them started their “walk training” before they turned two and were full-time walkers by two and a half. To this day, they have incredible stamina and patience and can out-walk most adults.

Again, I digress.

These days, Metro has a sane stroller policy. Parents can leave their child (and stuff) in the stroller and can use the lift and wheelchair area if it is not being used by a wheelchair passenger. It’s not a perfect solution, since parents sometimes must unhook, unpack, and fold in the middle of a ride, but it’s impossible to perfectly balance the needs of a diverse group of riders in a vehicle with limited capacity. And certainly, the current policy is significantly better than what I dealt with — so much better that I sometimes wish I had another baby just so I could take advantage of it.

OK, no I don’t.

There are so many examples of the positive impacts that thoughtful, people-focused agency policies have on riders. (There are also plenty of examples of the negative impacts of poor policies.) I hope Metro continues to incorporate feedback from folks on the ground into all of their decision-making processes.

5. Bus drivers are the best people. I’ve always been a bit in awe of bus drivers, so it’s beautiful to see that my kids feel the same way. I’ve written so much about the ways drivers have cared for and entertained our family over the years, I don’t have much more to say on the subject. Except this:

6. Seattle needs more public bathrooms. One of the most common challenges we deal with on our bus adventures is the restroom emergency. (The fact that the emergency is mine as often as it is one of my children’s is a minor detail.) Being stranded at a bus stop with a potty training kid who has to go (or a diapered kid who already did) is a not awesome aspect of busing with babies.

If the world were as it should be, there would be clean, safe restrooms at Link stations and all major bus stops. The world is not as it should be (so very not), so bus riders (and everyone else) must fend for themselves. I make it my business to know all the restroom options in the neighborhoods I visit frequently. My preferred restroom hierarchy: public (library, community center, government building, park [except YUCK]), private but accessible (hotel lobby, large restaurant), private but inaccessible (small restaurant or coffee shop with a key or code).

In case you’re not a restroom savant, there’s — obviously — an app for that.

7. Bus parents don’t “run errands.” When Chicklet was a baby, I was desperate to prove that our family could live like everyone else. Or, at least, that we could do everything other middle-class families did. This was in part because I was still in my “bus booster” phase (Who am I kidding? I will always be in my bus booster phase.) and was therefore more interested in proving that carfree living was possible than I was in analyzing its limitations.

Yes (thanks mostly to our proximity and access), my kids get to dance classes and sports practices and birthday parties and doctor’s appointments. Yes, we have food in our refrigerator and clothes in our closets and all the essential hygiene products in our bathroom. Yes, we go on fun outings. But the effort, time, and physical and mental energy that is expended to make all that happen can sometimes feel overwhelming. (Carrying capacity has always been, and as far as I can tell will remain, a huge challenge for me.)

And even with the basics covered, there are plenty of things we choose not to do, or do less often than we would like, because we don’t have a car. There are other things that we only do when we decide to rent a car.

What I have learned over these years is that we aren’t, in fact, trying to “live like everyone else” by bus. Instead, we are building and modeling a different way to live. And really, that’s always been the point.

8. The journey is the adventure. Sorry to resort to a cliché in an already cliché’ “10 things I learned” listicle, but folks, we’re talking transit here. Schlepping kids across town on the bus for an everyday errand like shoe shopping when you’re tired and pressed for time can be a hassle. But riding transit to go on an adventure is, well, an adventure.

When we take the bus (or train) to an event, or to a beach or park we rarely visit, we try new routes, walk in new neighborhoods, and enjoy new scenery. We spend our travel time focusing on each other instead of the road. These transit adventures have made some of our best memories as a family, and they’re a beautiful reminder of why we ride.

9. Our “sacrifice” is a privilege. While it’s true that our decision to live without a car requires determination and some amount of sacrifice, it’s also true that it wouldn’t be possible at all without a number of privileges lots of people don’t have. Living the way we do is possible for us because we have work that is flexible and accessible by transit, reliable internet access, and sufficient income. We are able-bodied and live in a centrally located neighborhood with sidewalks, pretty good transit, and nearby services. Because we are fortunate enough to own a home, our housing costs are stable, and, barring some unforeseen disaster, we can count on the access we need to keep doing this.

Back when I started my carfree adventure almost 15 years ago, Seattle was already an expensive city. But, it was possible (if challenging) for many carfree families to save enough on transportation costs to afford to live in a small space in the city. Now, city living is inaccessible to almost everyone. It is no longer a matter of tradeoffs or determination; it’s a matter of not having enough money to make it work, no matter how you get around.

And it’s not just about access. If any number of circumstances in our lives were to change, we wouldn’t be able to live this way anymore. If, for example, someone in our family developed a medical condition that required regular appointments or procedures or that made it difficult for them to walk long distances, we would need a car. If we decided to foster another child, who might attend a different school than our other kids and would almost certainly have family visits and other appointments outside our neighborhood (not to mention his or her own share of middle-of-the-night illnesses), we would need a car. If one of us started a job that involved a non-bus-friendly commute or that required us to travel around the region during the day, we would need a car.

For a few years now, I’ve been wondering about the point of it all. Why make a choice that constrains our lives in so many ways if it’s not a choice most others can emulate? Is there value in doing something so outside of the norm if it has little to no real impact, especially if we could be of more service to our community and extended family if we drove?

All I’ve got is this: You have to start somewhere. Sure, lots of people can’t get by without a car. But some of people can. And those people should. If they don’t, we cannot expect to see change in our lifetimes. Or ever.

So, the way I see it, our family needs to make the tradeoffs and feel the occasional discomfort and keep living this way for as long as we are able. We also need to fight like hell to make sure the privileges we have are available to more people. We must insist on affordable housing, so that working people can live in the city. We must insist on sidewalks in every community. We must advocate for more and better transit and safe bicycle infrastructure.

We must do this because living without a car should not be a choice only for the desperate or dedicated. It should be an option available to everyone.

10. Holding hands is awesome. The challenges of bus parenting change over time. You go from the physically exhausting infant period, to the squirmy, bathroom centric (and also physically exhausting) toddler phase, to the payment logistics and window-seat battles of the early school years, to the scheduling struggles of the older kid years, to … Lord only knows.

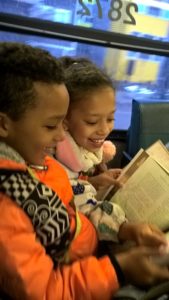

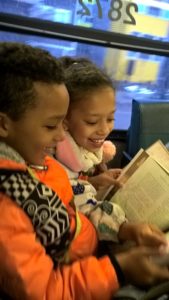

But the joys of bus parenting? Those remain constant. Playing “telephone” while waiting for the 8 on a rainy night. Reading books — together or separately — on the way to visit cousins. Running into school friends or church members or neighbors on almost every ride. Holding hands, sitting close, telling jokes.

I will continue to be grateful that we can do this, even on days when I’m exhausted and resentful and over it already. Because the truth is, busing with babies is beautiful. And we are so fortunate.