I started riding the bus alone at eight years old, younger than was common in 1980, and most certainly younger than is common in 2018. My initial solo bus trips were to school and involved a transfer downtown. After a few months of practice, I started branching out: riding to local stores, to my grandma’s apartment, to doctor’s appointments, even on adventures with my siblings. Even though at eight I was a bit on the shy side and pretty risk averse (OK, I still am), I never felt any reservations about taking the bus alone. I was confident in my abilities and proud that I could get around the city on my own.

Ironically, it was at around 14, an age when it is common to move through the world without the assistance of an adult, when I started feeling afraid to travel alone. This was the age when my body started to look like a woman’s body and, consequently, the age I first began to experience street harassment. My parents had prepared me well for the logistics of traveling by bus, but no one prepared me for life on the street as a woman.

Groping happened rarely, but leering and yelling were near constant. Back then, I didn’t know how to respond to the shouted comments about my body, the insults, the lewd jokes at my expense. I would cross the street to avoid encountering groups of men and hold my breath every time I passed a construction site. I would smile politely when disrespectful strangers pressed their phone numbers into my hand, because it didn’t take long to figure out that saying no to a man who feels entitled to your attention can activate rage. When men grabbed my arm, I would pull it away and keep walking (faster, and without turning back), so busy feeling scared and intimidated that it never even occurred to me to be angry.

But I’m angry now. Angry that experiencing this type of harassment so early in my womanhood changed the way I viewed myself and my right to move through the world. Angry that, when I was considering giving up my car 15 years ago, what gave me the most pause was not the logistics of how I would get where I needed to go, but the prospect of being on the street outside of normal business hours. Angry that my daughter, who will turn 11 in exactly one month, will soon face the same abuse I did as she ventures out on her own.

Even now, at several years past 40 (and mostly past the street harassment period of life), I regularly constrain my movements because of my gender. I repeat: I, a grown-ass strong, intelligent, capable, adult, regularly constrain the way I move through my city because of my gender. This is true for every woman I know, but, because I get around by bus, it’s especially true for me.

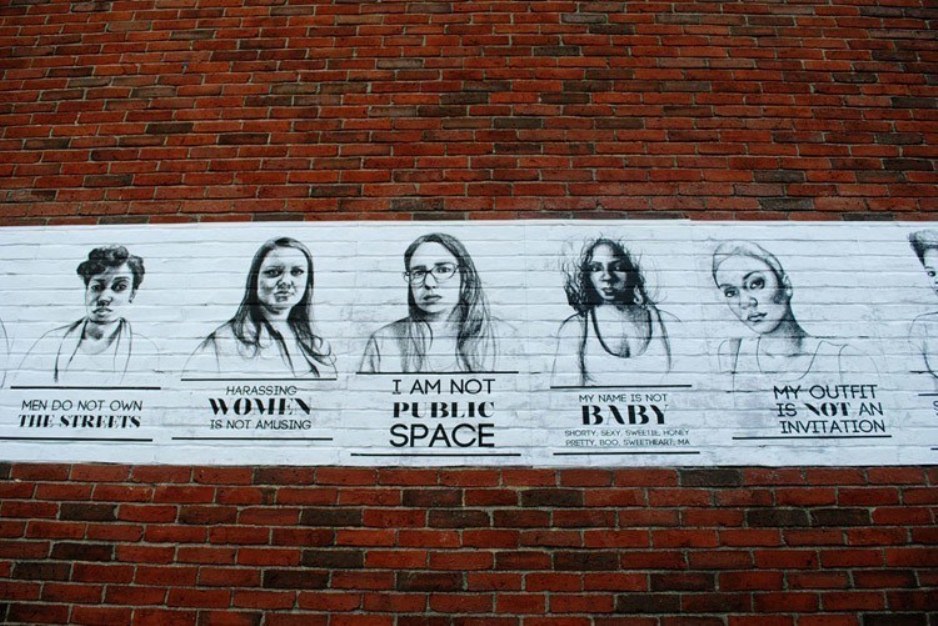

It goes without saying (but I’m gonna say it, just to be sure it’s clear) that harassment is not unique to public transportation. It’s a cultural problem that manifests itself in every corner of our society. (Ahem.) But the particular problem of street harassment happens more often to women who spend more time walking and standing outside. And yes, to women who share space with men on buses and trains.

Public transportation represents freedom. It provides mobility for everyone, regardless of age or ability or economic status. But women and girls will never be truly free to use transit until they no longer have to contend with abuse every time they walk outside.

Public transportation offers us the gift of contact with our community. But we cannot expect young women to embrace (or even tolerate) contact that is often demeaning and is sometimes threatening.

Public transportation, like any public good, is only as healthy as the culture it is a part of. If we want women and girls to embrace life on the ground, then we must pay as much attention to the misogyny that pervades our culture as we do to travel times and vehicle design.