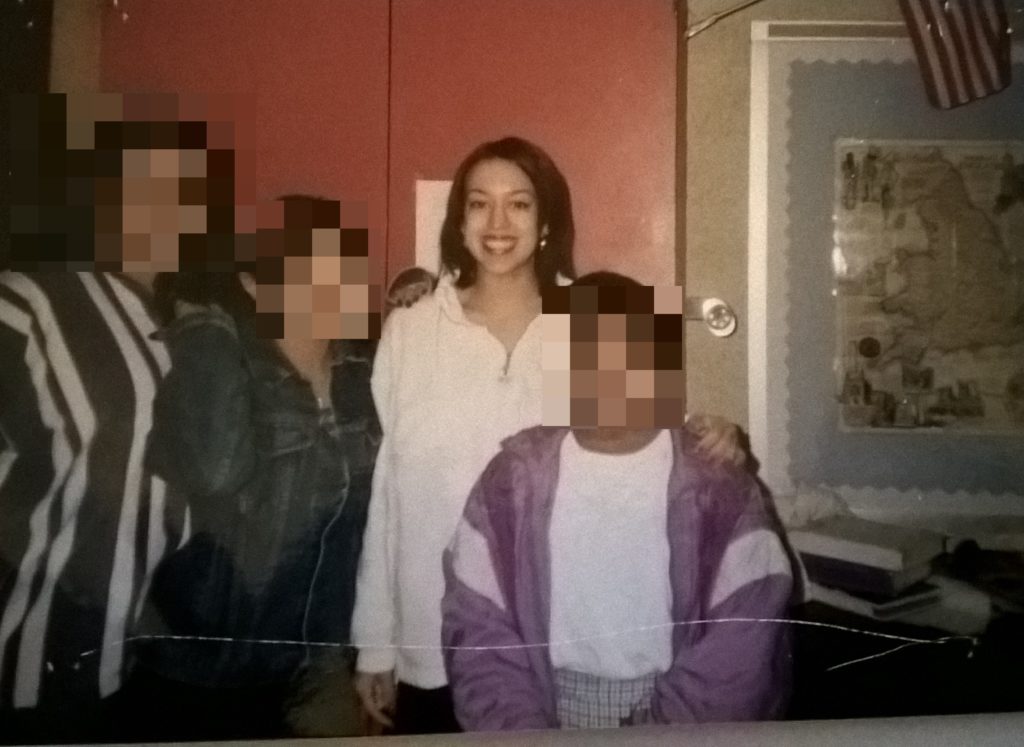

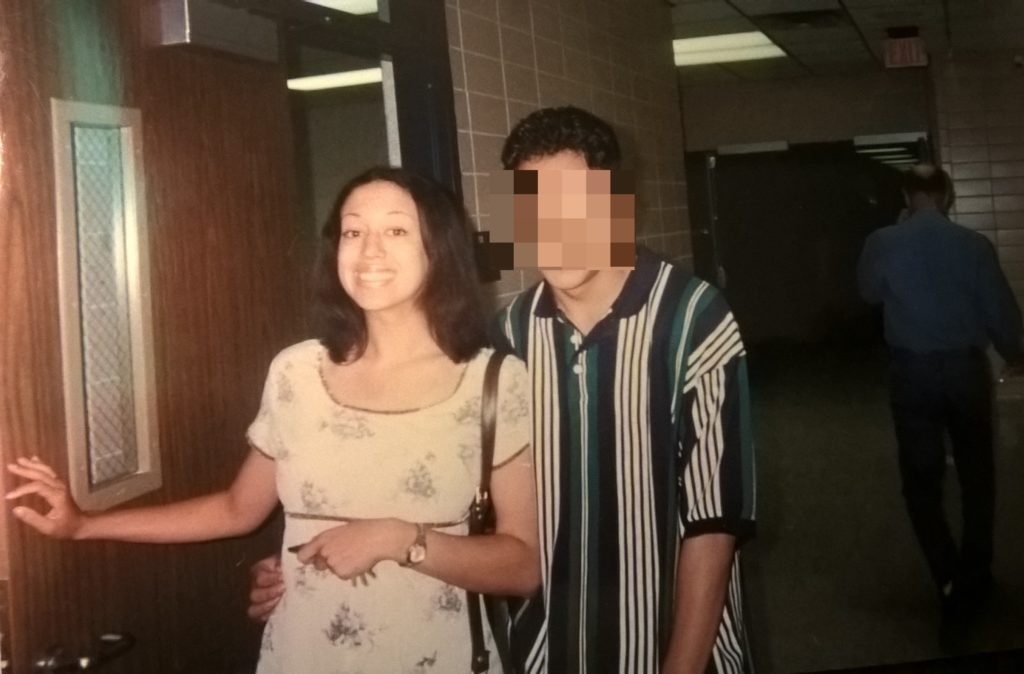

In the mid ’90s, back when I lived in Texas, I was a teacher. I came to the profession through a rather unconventional — though sadly, not particularly uncommon — path, and I didn’t last long.

I graduated from college with a BA in English, broke, with no clear idea of what I wanted to do for a living and exactly zero job prospects. Despite numerous visits to my university’s career services office, several half-hearted applications to “consulting” firms, and the moral low of applying for an entry-level communications role at Enron, I remained unemployed months after graduation. It was during this desperate time that I learned a school district at the northernmost reaches of the Houston city limits, comprised mostly of poor students of color, was hiring teachers.

It hadn’t occurred to me to apply for a teaching position, since I had no teaching certificate or teaching experience. (I had entertained — and dismissed — the idea of a teaching career early in college.) But this district was just as desperate as I was; it was experiencing an extreme teacher shortage and was therefore offering emergency certification. All that was required to apply was a bachelor’s degree, a mediocre GPA, and a background check.

After a short interview at the district office, I was hired to teach English at one of its four high schools. I started work at the beginning of the semester, without one single minute of training, without even a substantial meeting with the principal or the other teachers in my department. I was told what subject matter I was expected to cover, issued a couple of teacher’s manuals and a rolling cart, and sent off to do a job I had no idea how to do.

The cart, I should explain, was needed because I did not have a classroom. The school was overcrowded, and because I was a newbie and therefore low on the teaching totem pole, I was expected to “float”: teach each class in a different room, using the classrooms of more fortunate teachers during their planning periods. I had no desk of my own, no way to prepare lessons on the board in advance of class, and no place to meet with students or parents outside of class time. I didn’t even have access to a closet to store my coat and purse.

My classes were huge. Some had close to 40 students. On days when everyone showed up, there weren’t enough desks, and I would scramble at the beginning of the period in search of rare extras from other classrooms. A couple of times a month, a new student would show up. At least as often, a student on my roster would disappear.

The school had recently moved to “block” scheduling and for some reason could not figure out how to implement more than one lunch period with this new schedule. So, all 3,000 students ate lunch at the same time. There was not enough room for 3,000 people to eat in the cafeteria, so students ate throughout the school building. The staff was expected to supervise the students during lunch, to ensure that they followed school rules. This exercise in futility was called “lunch duty.”

Back in the mid 90s, state tests were just starting to become a thing. Texas’s test, then called the TAAS, was a big deal for districts and was an especially big deal for our district, since our scores were quite low. In my second year at the school, I was required to teach a daily, semester-long class on this test. (In block scheduling, a semester is the equivalent of a full school year.) I repeat: I was required to teach a daily class about how to take a test. This was in addition to the math test prep that I, an English teacher, was required to do with all of my classes for the first 10 minutes of every period.

These were the conditions under which I began my short-lived teaching career. It is clear to me now (even more than it was then) that I was not set up for success. Given the circumstances, I could not have given my students what they needed and deserved no matter how hard I tried. But the thing is, I didn’t really try.

I had no idea how to be a good teacher, and I didn’t ask for help. I didn’t find a mentor, or attend trainings, or read books about best practices for classroom management or lesson preparation. Instead, I prepared lessons at the last minute and “winged” my way through almost every class. I looked forward to my students completing required readings so that I could show the movie version of the story and avoid teaching for an entire class period. Any (rare) moments that I wasn’t required to spend with students I spent in a locked classroom with a few other young teachers, talking about how much we hated our jobs.

Once, I shared a lunch duty post with a PE teacher, a man in his 50s with many years of experience. In the course of our conversation, I complained about the chaos at the school. He agreed with me about the craziness but seemed resigned and wholly unconcerned. “These kids are trash,” he told me matter-of-factly. He only worked at our school, he explained, because the district paid more than districts with more “desirable,” students. He was looking forward to retirement, but in the intervening years, he would earn his paycheck honorably, by “giv[ing] them a basketball.”

What did I say in response to this man’s disgusting comments? Absolutely nothing.

At the beginning of every semester, I received individual education plans (IEPs) for all of my students with special needs. As their teacher, I was required to adjust my teaching style to suit these students’ learning styles. I know for sure that I did not do that. I did not even know how.

I rarely called parents, in part because many of my students were from non-English-speaking families, and I lacked the necessary communication skills, but mostly because I wasn’t organized or proactive enough.

Despite these (and many other) deficiencies, both of my formal reviews were solid: in the B+ range. This fact alone tells you all you need to know about the level of expectation and the amount of oversight in that school.

It wasn’t all awful. I showed up every day, despite the terrible conditions and the depressing, prison-like atmosphere. I tried to help my students understand how their schoolwork applied to their lives and their futures. I managed a few creative and inspired lessons. And I am certain that some of my students learned something of value from me.

After two years, I accepted that I was not cut out to be a teacher and moved on to a profession I was better suited for. (A decade later, I moved on again, but that’s a story for another time.)

Now I have children in school, and I am dependent upon teachers to care about them, to see their humanity, and to create safe and stimulating learning environments. Now I understand better than ever what my students deserved, and just how much I failed them.

There is no way to fix the mistakes I made. All I can do now is ask myself what I owe.

Certainly, I owe a commitment to the children who are enrolled in public school now. I owe support and encouragement to those teachers who take seriously their responsibility to educate our children. (This support must also manifest in the public arena, by demanding that our leaders fund reasonable working conditions and decent salaries.)

Also, I owe the truth.

The truth is, we don’t value all children equally. The truth is, we are willing to accept substandard education for poor students and students of color.

The truth is, we are throwing away human beings.

What are we going to do about it?