I live in a gentrified neighborhood. The Central District was once the heart of Seattle’s Black community. Now, skyrocketing housing costs and rising property taxes have pushed all but a very small number of Black folks out of the neighborhood. The circumstances that led to displacement in the Central District are not unique, but the community was. And what has been lost can never be replaced.

As a (mixed) Black person who can afford to live here, as someone who did not grow up in this community but who is the daughter of a man who started his life mere blocks from where I now live and the granddaughter of a woman who lived here for a good portion of my childhood, my relationship to the changes is complicated. I am angry and sad about the loss of longtime residents and of this neighborhood’s identity as a black community, but I also understand that I am only here because of my own privilege. And I recognize my status as a relative newcomer, having purchased my first home here after prices had already risen beyond the reach of many longtime residents.

But this post isn’t about my complicated relationship to my neighborhood. (That post is coming; I only need another decade or so to process all of my thoughts and feelings.) It is about the community’s most recent loss.

The Promenade Red Apple Market, my neighborhood grocery store, closed in September. The property the store was leasing was purchased by a developer, and that developer’s vision did not include Red Apple. The store sat empty for several months after its last day of operation. Then, last month, the bulldozers came.

The loss has been difficult logistically for our family because there is no longer a grocery store within walking distance of our home. But it has been much more difficult emotionally. It seems strange to say, but I am in mourning.

I’ve shopped at the Promenade Red Apple regularly for 15 years (and occasionally for even longer). In those years, I have visited the store close to 2,000 times. Red Apple wasn’t perfect. The many customers who walked to the store were forced to cross a giant parking lot that was at least as big as the store — and never more than half full — to reach the front door. Prices were (understandably) higher than you would find at a large chain. The produce wasn’t always the best quality.

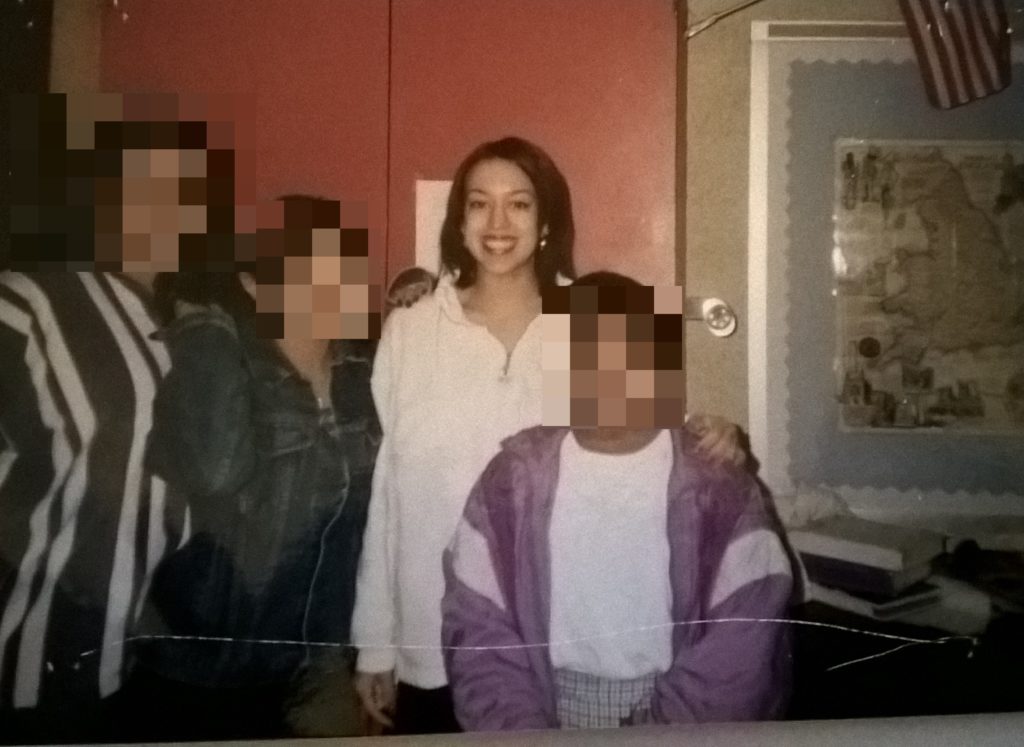

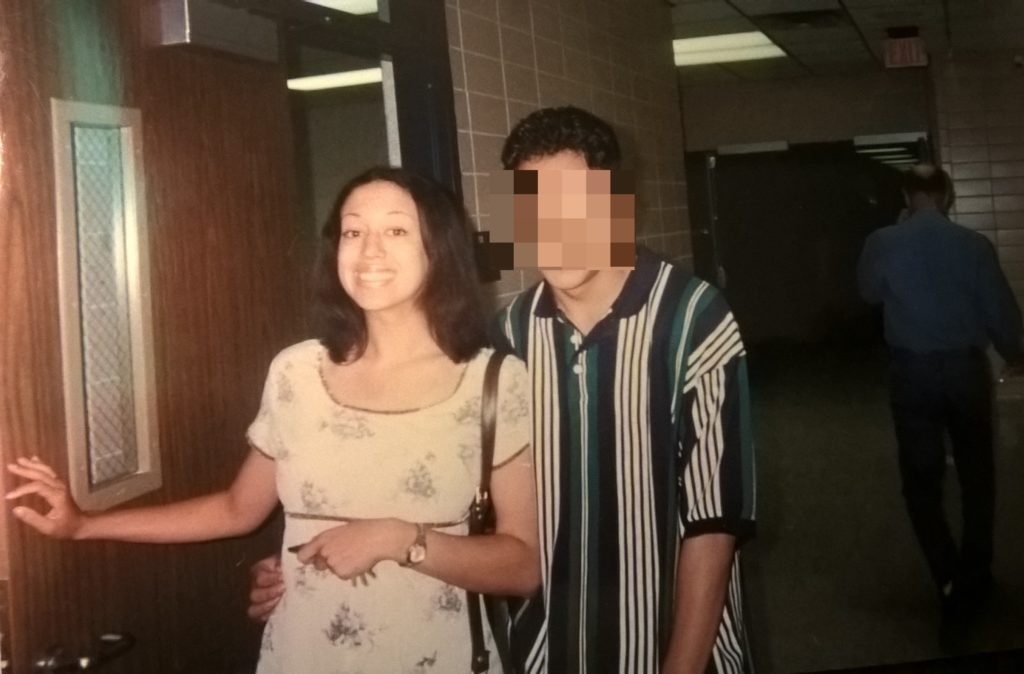

But Red Apple was much more than a grocery store; it was a part of the community, a place where people felt seen and known and valued.

The management and staff of Red Apple showed that they valued people by the products they chose to stock, continuing to carry foods that are culturally significant to Black folks long after the demographics of the neighborhood had shifted.

They showed that they valued people by the atmosphere they created, playing “the best soul music in the city” in the aisles at all times, elevating even a quick trip for a few forgotten ingredients into a spontaneous dance party.

They showed that they valued people by affirming our dignity, allowing anyone to use the restroom or come inside to warm up or cool off.

They showed that they valued people by asking about our days and asking after our loved ones.

They showed that they valued people by celebrating with us, hosting holiday parties and Easter egg hunts and backpack giveaways year after year after year.

The plans for the new development look lovely. There will be better pedestrian access and new apartments and even (if the early designs are followed) some sort of outdoor plaza. More housing in a city facing an extreme housing shortage, a built environment that makes walking safer and gathering with others easier — these are important improvements.

Except.

Except accessible design does not make a place accessible. And physical beauty is not the same as soul.

The new apartments will be unaffordable to all but the very wealthiest slice of this city. The new stores will likely be as well. If history is any guide, gathering will be restricted to those who are perceived to belong.

If there’s a grocery store in the new development, it will surely have perfect produce and squeaky clean floors and plenty of selection. But I’m guessing it won’t carry pig feet or turkey necks. And I know for sure it won’t host a holiday party where customers can do the Cupid Shuffle with Santa.