In the US, we are trained to believe that we can be self-sufficient—that if we just work hard enough, save enough money, buy enough insurance, hoard enough toilet paper, or build tall enough fences, we can insulate ourselves from what is going on “out there.”

This has always been an illusion.

The truth is, most of us eat because other humans grew and harvested food, then processed, packaged, shipped, stocked, and sold it to us.

The truth is, even the most “self-made” among us were brought into this world and then kept alive by other humans (not to mention the ecosystems that sustain us).

The truth is, if someone drops a cigarette in a drought-stricken forest, the smoke will affect our lungs, too.

The truth is, if one of us is sick, none of us is well.

These are the lessons that the pandemic has taught us—and that have always been available on the bus.

On a cold morning last January, when Covid cases were still rising in King County, and every bus ride felt like both a gift and a risk, Busling and I watched a not-uncommon scene unfold at a stop. While we waited for the 48, an 8 pulled up and parked. The driver turned on the hazards and opened all the doors, then walked to a seat near the back, to a sleeping passenger whose mask was on the floor near his feet.

The driver tapped on the seat until the passenger opened his eyes.

“Sir! Sir! I need you to put a mask on.”

The passenger looked blankly at the driver for a moment before his chin drooped to his chest and his eyes closed again.

The driver tapped on the seat again. As he tapped, he repeated, “Sir … sir! I need you to put a mask on.” The passenger—60-ish, clearly intoxicated, and very likely unhoused— continued to open, then close, his eyes. He never spoke or moved to retrieve his mask.

Finally, after several minutes, the driver gave up. He left the passenger and mask where he had found them, returned to his seat, closed the doors, and drove away.

I have seen versions of this scenario play out many times on my Covid-era transit rides. And we have to talk about it.

What I love most about the bus is that everyone belongs. The world I’m trying to build is one in which public transportation is free, safe, and accessible to all. This means that I support any and all efforts to decriminalize transit infractions. It means that I don’t have a problem with someone riding the bus to stay warm (or cool). AND it means that no one should be exposed to a contagious, deadly disease while riding—or driving—a bus.

Every time something happens on transit that feels threatening to me or my children, I do a gut check. Do I want to keep doing this? Do I want to keep doing this in a pandemic? Usually, my initial response is a reflexive, almost visceral urge to turn away. I want to stop riding the bus, stop being exposed to risk. What I really want is to stop being exposed to reality.

But then I return to myself. I remember.

It’s true that there’s nothing inherently unsafe about transit. (Cars are far more dangerous, especially to children.) But the bus requires us to experience our fellow humans directly, to share the ride with the people we share the world with. If one of my fellow passengers is hateful, or harmful, or in distress, I will experience their suffering in real time.

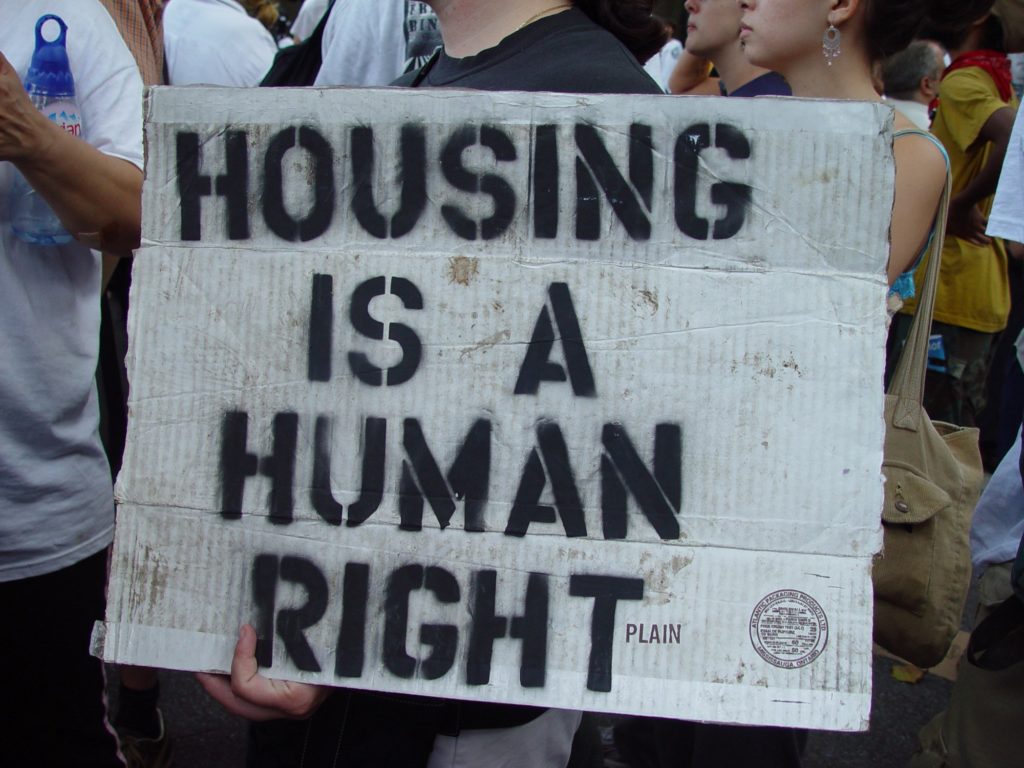

Because here’s the thing: We can’t create safe communities without first ensuring that everyone’s needs are met. A society that leaves thousands of human beings without shelter from the elements harms everyone, including those who are comfortably housed. Including those whose jobs require them to serve the public.

The driver and passengers on that early morning 8 were faced with unnecessary risk and few safe (or satisfying) options for addressing it. This fact should galvanize us—not to create more rules or more enforcement mechanisms, but to end the conditions that created the situation. The problem isn’t what we should do about a passed-out passenger on the bus without a mask. The problem is, we haven’t figured out that our well-being is connected to his.

We cannot look around at the misery in our city and decide that the answer is to isolate and insulate ourselves—or to turn on those who are suffering. We must see our neighbors in distress as a sign that we are all sick. Then we must do what’s necessary to heal.