A few years ago, the Climate Accountability Institute published a study that said 100 companies are responsible for 71% of global emissions. Since then, there’s been a growing chorus of voices insisting that our individual environmental choices (climate-related and otherwise) are meaningless—that we should redirect our focus from regulating individual behaviors and instead regulate major polluters. In other words, stop asking individuals to take shorter showers while allowing Nestle to drain aquifers at the rate of 400 gallons per minute.

I call BS.

It’s not that I disagree with the premise. Of course major polluters must be regulated (or better yet, eliminated). Of course individual choices cannot counteract the destructive impact of multinational corporations. But anytime we try to simplify or externalize a cultural problem, we’ve limited our ability to address it.

First of all, we don’t have to choose. We can stop Nestle from destroying wetlands and take shorter showers. And pretending that there is no connection between our individual actions and the health of our planet is both disingenuous and spiritually dangerous.

Last year, during the uprisings for racial justice, the internet and airwaves were filled with people talking and writing about systemic racism. This was (and still is) important and necessary. But what was almost completely missing from that collective conversation was self-reflection. Very few of the people pointing at the problem were asking, “How does the racism in our culture show up in me? How am I influenced by it? How do I perpetuate it? What practices must I adopt to identify and address it?”

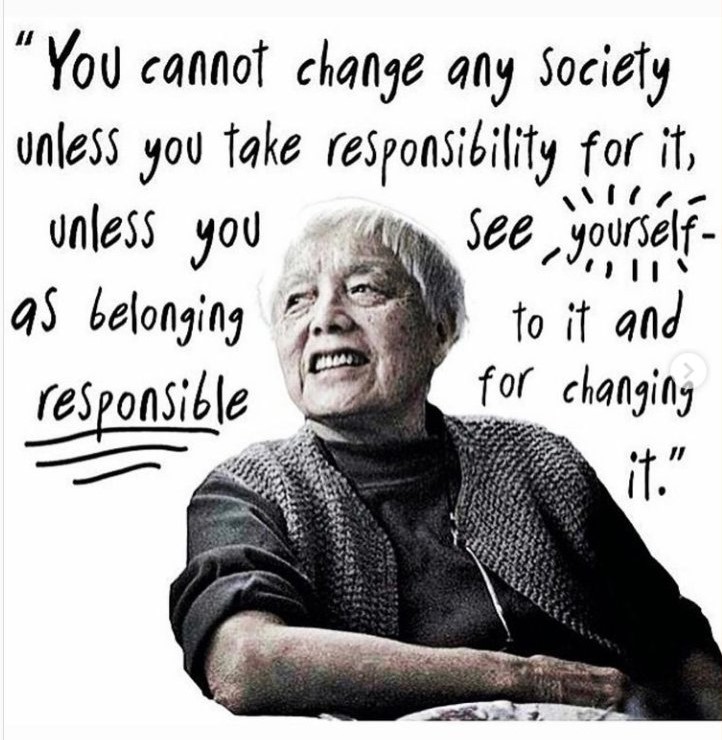

Grace Boggs says we must transform ourselves to transform the world. Racism is a systemic problem, and systems are upheld by people. If we see racism as a problem “out there,” we will never eliminate it, no matter how many institutions we topple.

Just as racism will persist as long as it continues to live in individual humans, environmental harm will persist unless and until we change the way we relate to the ecosystems we are part of. On a basic level, we must acknowledge that many of the corporations doing damage to the planet are—directly or indirectly—supported by our individual choices. But this is deeper than counting damage or assigning blame.

One of the many lessons I learned from my time as a foster parent is that acts of care build love. My love for Baby S was the result of the daily work of caring for him: brushing his teeth, preparing his meals, cleaning his messes, comforting him when he woke in the night. My choice to love him despite the certain knowledge he would not be in my life forever might or might not have benefitted him, but I know for sure that it transformed me.

Prioritizing the planet in our big and small choices is important, even if the impact of those choices is “meaningless.” Concrete acts of care can help give us a sense of control and purpose in a scary, out-of-control time. And those acts will help us build a relationship with the land that sustains us.

It might be true that my own small choices don’t change anything in the material sense. (It also might not be true, since we can never know the impact of our actions, and because small actions can and do spread.) But what I know for sure is that every time I make a decision that is rooted in love for the earth (and in particular, for this land), it deepens my understanding of and appreciation for the living world. Humans who appreciate the living world will build cultures that prioritize its flourishing.

This doesn’t mean that we should ignore the big picture in favor of personal purity. We can still vote and protest and pressure and boycott and protect. But the impulse to protect stems from love. And I am willing to bet that any person putting their body on the line to stop a pipeline or preserve an old-growth forest has a relationship with the living world.

I’ve spent these past several years feeling slightly ashamed for the energy I put into small decisions. But I’m beginning to see that care and intention as part of the cultural transformation that is necessary to move us to the world we dream of. This transformation requires us to tell a different story about who we are and who we want to be; a different story about success, health, wealth, prosperity, and a good life; and a different story about self-interest. It requires us to slow down and pay closer attention to every engagement, every outing, every moment.

We can take our time and be intentional, instead of rushing through everything. We can prioritize care over convenience and do less, with love. We might not be able to measure the impact, but we will feel it.